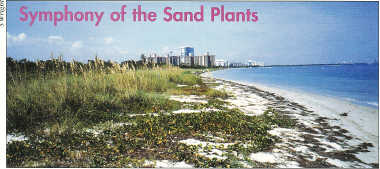

Symphony of the Sand Plants

Cynthia Lane, Ph.D., Former Conservation Ecologist

|

| Contrast of natural and developed South Florida coast |

I grew up in a small Wisconsin town that had no symphony, at least not in the accepted classic sense. Instead it had a symphony of natural wonders: ponds hosting the fugue of the frogs and bubbling streams composing original water music. It was not until I moved to Miami that I heard my first classical symphony. The tone and volume were different from the Afro-Cuban and West African music I knew know so well, but the synergism was the same. At times, I heard a single instrument, then heard others join in, lyrically creating the whole.

|

| Sea oats surround skeletons of Australian pine |

I remembered this experience last September as Sam Wright and I walked to our research sites within the edge of Hurricane Michelle churning just offshore. The sky and ocean loomed, a contrast of dark and frothy white. Halophytic (salt tolerant) dune plants struggled to hold the sand, but the high tide and breaking waves exposed their roots. Spray hit my face and the wind whipped my hair. My lips tasted of salt. Yet when I bent down to examine a plant, I could feel calm air near the ground. This is the phenomenon that forms dunes — calm air in the shelter of the dune plants allows the sands to fall. Only a foot above, the wind whipped the sea oats (Uniola paniculata) into a wild dance as sea grapes (Coccoloba uvifera) did a slower funk. Plants moved individually, yet in unison, forming a whole greater than the parts, a symphony of sand plants.

|

| Coccoloba uvifera (sea grape) |

We were searching for the federally endangered beach clustervine (Jacquemontia reclinata). A wiry, tough vine, it hunkers down out of the wind, toughing out the heat and sun. By growing inland from the halophytic zone, Jacquemontia avoids being buried by sand or washed away by wild seas and high tides. Surprisingly delicate white flowers lace the ground. It was once abundant on the east coast of South Florida, but despite extensive efforts by Fairchild conservation staff, local land managers and naturalists, only nine small natural populations have been found.

|

| Blossoms of the federally endangered beach clustervine Jacquemontia reclinata) look like stars. |

Intense coastal development and recreational use have drastically reduced the extent of the once contiguous dune ecosystem. A 1993 survey of intact coastal areas indicated that only a small percentage of original coastal vegetation had escaped destruction. The remaining coastal vegetation is heavily impacted. Raking the beach to pamper sunbathers destroys the waving grasses quicker and more often than the occasional storm. Beach stars (Cyperus pedunculatus) are the first to be uprooted as trampling widens the beach area. Non-native invasive species often outcompete native beach species. Luckily, some, such as Australian pine (Casuarina spp.), are not as adapted to hurricanes as the natives. The high mortality of these species following Hurricane Andrew gave our locals another chance.

I wonder if the thousands of beach goers know the musicians of these dunes. At most public parks, balancing natural resource preservation with recreation is a constant challenge. Last year there was pressure to put a ballpark in a coastal park. Cute and cuddly animals tend to be more successful in capturing public interest than smaIl plants. While everyone jumps with excitement as dolphins swim by, far rarer plant species bloom unnoticed just a few feet behind - gems unlike any, anywhere, anytime.

|

| Cyperus pedunculatus (beach star) - a cymbal splash on the beach |

On that day last fall, Sam and I were thankful for the wind. The back side of a dune on a hot day in Florida is as bright and intense, and in many ways as unpleasant, as the 40° below zero days back home. But even on the hot days we love the unique sonatas of the dune. And as Sam says, “It sure beats being in a cubicle.”

|

| Okenia hypogaea (beach peanut) |

We share our fascination with these dune ecosystems with the land managers who oversee them. Steve Bass, a land manager in Palm Beach County, has worked for years to protect coastal areas and educate people about them. Fairchild's Conservation staff is working with him and a group of teens to restore a section of the dune which will include plantings of Jacquemontia. We've started working with Ernie Lynk (Miami-Dade County) to evaluate the effects of trails and foot traffic on rare plants. He suspects that while unauthorized trekking through sensitive areas crushes dune plants, the effect of human activities is not always negative. Activities that result in the reduction of competitive woody species may be beneficial to low growing plants like Jacquemontia. Some plants, like Okenia hypogaea (the beach peanut), seem to flourish with a little rough treatment. Okenia is thickest in an area where Britney Spears recently shot a video. It appears that soil disturbance or the crushing of competing species were conducive to Okenia growth. Then again, maybe it was the music.

|

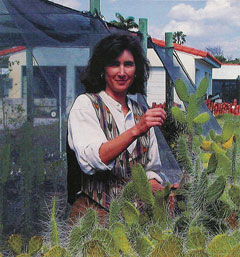

| Dr. Cynthia Lane examines a Opuntia corallicola, part of the endangered species collection at the Center for Tropical Plant Conservation. |

Sea oats, abundant and waving in unison; the slow and steady undulations of the hardy sea grape; Jacquemontia and beach peanut vines recklessly soloing as they reach for space; the cymbal crash of beach star; shifting sands; the wind as maestro. This is a symphony I have seen many times. Different musicians, different songs - silver maples and nettles, oaks and prairie grasses, along with the maestros of flood and fire. But these composers and musicians are disappearing rapidly. Conservation biologists and ecologists warn that we face one of the greatest extinction events this planet has ever experienced. Ignored, the symphony of the sand plants will likely be reduced to a few common species. Is this the legacy we leave for future generations? Do we condemn them to one violin and cello? I for one urge: let's save the symphony.

Several Fairchild Tropical Garden staff members work in collaboration addressing aspects of coastal conservation: Dr. Jack Fisher; Sam Wright, Hannah Thornton, Elena Pinto-Torres, Meghan Fellows, Jennifer Possley, and Dr. Javier Francisco-Ortega.

Garden Views Spring 2002