Dransfieldia, A New Genus for an Old Palm

by Scott Zona, Ph.D. and Carl Lewis, Ph.D.

The last palm genus to be named was Satranala from Madagascar, described in 1995. In fact, recent studies in palms support a reduction in the number of genera. For example, the genus Calyptronoma was merged into Calyptrogyne last year as a result of DNA studies led by Fairchild's Dr. Julissa Roncal. Rumors of a new genus had palm growers and palm scientists alike buzzing with excitement. Now the new genus has been given the name Dransfieldia in honor of Dr. John Dransfield, world authority on palms and the recently retired head of Kew's palm research program.

The story of Dransfieldia began in 1ndonesian New Guinea in 1872, when the great Italian botanist, Odoardo Beccari, collected a new palm there. He called it Ptychosperma micranthum because it had flowers and fruits that look typical for Ptychosperma. However, the leaflets were unusual in that they tapered to a point, unlike the jagged-tipped leaflets that are typical for Ptychosperma.

The species did not reside for long in the genus Ptychosperma. In 1883, the then Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Sir Joseph Hooker, read Beccari's description of the new species and proposed that it actually belonged in the genus Rhopaloblaste. Even in that genus, the species seemed out of place. The male flowers and seedling leaves were quite different from other species of Rhopaloblaste. It was not a good fit, but the species was so obscure and New Guinea was so far away that no one paid any notice.

Then came the indomitable Dr. Harold E. Moore, of Cornell University, who was the greatest palm botanist of the mid-20th century. In 1970, Moore examined Beccari's collection in the herbarium in Florence, Italy. Based on his study of that single specimen, Moore concluded that the species was neither Ptychosperma nor Rhopaloblaste, but that it in fact belonged to Heterospathe. Beccari's collection included part of the crownshaft which is absent in all species of Heterospathe, but despite this anomaly, Moore shoehorned the species into Heterospathe, where it remained, unnoticed and nearly forgotten...

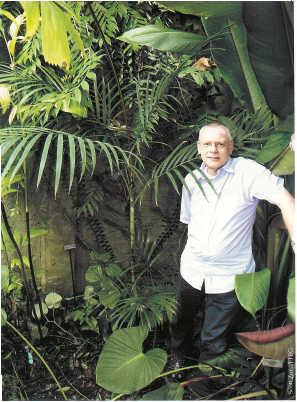

In 2000, Bill Baker and Indonesian colleagues Charfie Heatubun and Rudi Maturbongs co11ected specimens of a palm from New Guinea that looked like a strange species of Ptychosperma. They sent duplicate dried collections to Fairchild, because Dr. Scott Zona is writing the taxonomic account of Ptychosperma for the Palms of New Guinea project. The mystery palm looked like none of the species of New Guinea Ptychosperma that Zona had studied in Florence. Baker and Zona very nearly described it as a new species of Ptychosperma, until Baker, while examining Heterospathe species in Florence in 2002, found that the mystery palm was a perfect match for Beccari's original specimen. Baker's mystery palm was only the second collection of the species since Beccari found it in 1872. The tale might have ended there, as the story of the rediscovery of Heterospathe micrantha, except we did not rediscover it: Heterospathe micrantha has been growing in Fairchild's Windows to the Tropics Conservatory since 1998.

This palm probably entered the nursery trade as Australian collectors explored the rainforests of New Guinea. Fairchild acquired a specimen in 1998, and planted it in the Conservatory. Dr. Carl Lewis analyzed its DNA as part of his research on palm evolution. Lewis' analysis turned up some very surprising results: This species did not belong in Ptychosperma, nor did it belong in any genus related to Ptychosperma. Lewis' results were confirmed by Maria Norup, of Kew, who also eliminated Heterospathe and Rhopaloblaste from consideration. Both analyses confirmed the unexpected. The DNA matched no known genus!

With definitive DNA evidence in hand, we reassessed the palms unusual combination of morphological characters and concluded that we had a new genus. Dransfieldia represents a new lineage in the family, a new branch of the palm family tree. It has no close relatives in New Guinea; in fact, its closest relatives may occur in New Caledonia, more than 2000 miles away.

The most amazing part of the story is that the genus was hiding in plain sight. The original specimen has been in the Florence herbarium for 130 years, and the species has been in the nursery trade for nearly a decade. Unraveling the puzzle of Dransfieldia micrantha was a collaborative effort that took fieldwork and exploration, detailed study of old and new herbarium specimens and modern molecular techniques. There is a powerful synergy in combining historical knowledge with modern findings. Our story is a reminder that there are new discoveries still to be made in palm botany, and that the best work combines techniques both new and old.

DHTML JavaScript Menu By Milonic.com

Copyright © 2007 Virtual Herbarium - All rights reserved

11935 Old Cutler Road, Coral Gables, FL 33156-4299 USA

Phone: 305-667-1651 • Fax 305-665-8032