Night Moves

Scott Zona, Former Palm Biologist

| |

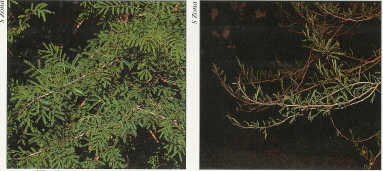

| The legume Acacia totuosa in the day... | ...and at night; with leaflets exhibiting nyctinastic closure (‘sleep movement’). |

Do plants sleep? That's a question without an immediately obvious answer. A more relevant question might be: If plants did sleep, how would we know? It is becoming increasingly clear to botanists that plants experience circadian rhythms just as humans do. “Circadian” means “around the day,” and this word describes rhythms or cycles that organisms experience on a daily basis. These cycles are not always sleep-like in the human sense of metabolism slowing down and the organism becoming inactive. On the contrary, a lot goes on under cover of darkness.

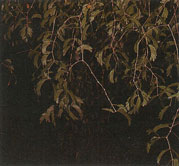

Some plants appear to shut down and go to sleep at night. Sleep movements, known to botanists as “nyctinasty,” are especially common in certain plants of the bean family (Fabaceae). At sundown, the leaves of these plants fold up or droop down. The corresponding unfolding of leaves comes about at dawn. Bean leaves are generally compound, i.e., a single leaf is composed of several leaflets. At the base of every leaf and every leaflet lie swollen, hinge-like structures called pulvini (singular: pulvinus). The pulvini are specialized regions containing large, water-filled cells. The water in these cells can be pumped in or out of the pulvini, resulting in changes in turgor. As turgor is decreased, a pulvinus acts as a hinge, allowing the leaf to droop; as turgor is increased, the leaf returns to its daytime position. The folding or drooping of leaves makes the plant look like it is “shutting down for the day,” so it is no wonder that nyctinasty is commonly likened to sleep. The functional or evolutionary reason behind nyctinasty is still unknown.

|

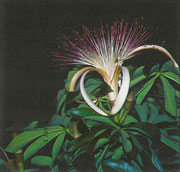

| The spectacular nocturnal blossom of Pachira aquatica. |

Leaves are not the only organs with circadian movements. Flowers too can open at dawn and close with the setting of the sun. The Tribulus cistoides is one such example: Its bright yellow flowers come to life at sunrise and face into the sun. During the day, as the sun appears to move across the sky, the flowers of Tribulus track the sun like little satellite dishes, reorienting themselves so that they always face into the sun. When the sun drops below the horizon, the flowers close. Some species of day-flowering plants can open and close their flowers for several days in succession.

The setting of the sun does not always bring about the closure of flowers. Indeed, it can have quite the opposite effect. Nightfall is the cue for many plants to begin reproductive activity. Four-o’clocks (Mirabilis jalapa) earn their common name from the time at which their flowers open, about four o’clock in the afternoon. (The ones in my garden, for some reason, seem to be on Greenwich Mean Time — they don't open until around nine o’clock at night.) Four-o’clocks are pollinated by evening-flying moths that are attracted to the sweet fragrance of the flowers.

The African baobabs (Adansonia digitata) announce their flowering to Garden visitors by dropping withered and brown flowers onto the tram path beneath the trees. One has to observe the tree at night to see the dazzling white flowers at their best. Shine a flashlight into the crown of the tree to see the fluffy white flowers dangling singly from the branches. Another tree that is best seen at night is Pachira aquatica. Caught in the beam of a flashlight, its flowers look like exploding fireworks. They are a mass of stamens that are white at the base and deep red toward the tips. These airy flowers can be a foot across and have the aroma of bananas. Both trees are pollinated by bats. In their native habitats, these trees are visited by bats which lap nectar from the flowers and become dusted with pollen. As they forage from flower to flower, they transfer pollen from one flower to another.

|

|

| Bulnesia arborea (Zygophyllaceae) in the day... | and at night, with leaflets “asleep”. |

Perhaps the strangest of all night-flowering plants are the aroids — philodendrons, anthuriums, and their kin — members of the family Araceae. The unifying feature of this large, mainly tropical, family is the way their tiny flowers are arranged on a fleshy spike (called a spadix) that is surrounded by a modified leaf (called the spathe). The spathe-and-spadix ???Bauplan is found in virtually all members of the Araceae. Many aroids are night-blooming, although evidence of flowering is not so much a physical change in the appearance of the flower stalk, but rather a physiological change. When these aroids are in full bloom, the flower stalk generatesheat. Biologists believe that the heat generated by the flower stalk helps volatilize the attractive fragrance and keeps night-time visitors warm.

Night-blooming aroids attract beetles, which swarm on the spadix and crawl toward its base, seeking warmth and shelter in the chamber formed by the spathe. The spadix bears staminate (male or pollen-producing) flowers above and pistillate (female or ovule-bearing) flowers toward its base. These night-bloomers are protogynous, meaning that the pistillate flowers mature and open before the staminate flowers. An incoming beetle bearing pollen and crawling around the base of the spadix is bound to rub some pollen onto the receptive pistillate flowers. To ensure that the beetles stay long enough in the chamber, aroids provide food for their guests in the form of fleshy sterile tissue, nectar, or sterile flowers. Plentiful food and privacy put the beetles in an amorous mood, and mating among beetles often occurs in the inflorescence chamber. By morning, the pistillate flowers are well on their way to producing fruits and seeds, and then and only then do the staminate flowers release pollen. The spadix may also exude droplets of liquid that act like glue, sticking the pollen grains to the beetles. As the beetles exit, they become covered in liquid and pollen and search for their next night-time rendezvous.

The all-time champ in heat production is a familiar plant to gardeners here in South Florida. It is another aroid, Philodendron selloum, a common landscape plant from Brazil. Its big, dissected leaves are its most attractive feature, so few people realize that this species produces flowers. Although its spathe and spadix are fairly large, they are borne on very short stalks at the base of the leaves. During the evening, the spadix of E selloum heats up, reaching its peak at about 7 p.m., at which time it may be 45° or 46°C (ca. 115°F), or as much as 30°C above ambient temperature! Philodendron selloum is remarkable not only for the feverish high temperature which it attains, but also for the way in which it generates the heat. Most heat-generating plants do so by hydrolyzing stored starch - by burning carbohydrates, so to speak. But the metabolic process in E. selloum is different. This plant metabolizes stored lipids, i.e., it burns fat. JennyCraig, take note. Lipids store more energy than carbohydrates — about twice as much — and allow the Philodendron to achieve its record temperature.

All around the world and in our own gardens, as nightfall blankets the land, some plants appear to sleep, while others awaken in rhythmic procession. Flowers gape and exhale their cloying fragrance. Amid the flutter of wings, tongues lick lips sticky with nectar. We lock our doors and close our eyes to sleep, but outside, all around us, is the rustle and hum of life.

Garden Views November 2000